The term digital sovereignty has become a broadly used term lately though this was already in 2020 a concern.

The WEF defines digital sovereignty as follows:

Digital sovereignty, cyber sovereignty, technological sovereignty and data sovereignty refer to the ability to have control over your own digital destiny – the data, hardware and software that you rely on and create.

Chatgpt would summarize a more general definition, stripping away institutional framing, which would read like this

Digital sovereignty refers to the ability of states, organizations, or individuals to independently decide, control, and shape how digital technologies, infrastructure, and data are used and governed, without undue external dependency, and in line with their own legal, political, and societal values.

Crucially, digital sovereignty does not mean digital autarky or isolation.

It means having the freedom to choose including the freedom to cooperate globally without surrendering control of your digital infrastructure and services.

Digital Sovereignty in the European Context

For the European Union, digital sovereignty is closely linked to strategic autonomy. It reflects the capacity to make independent decisions in the digital sphere while remaining an open, rules-based economy. It’s not only about economic interest but roots into the respect for social values.

In practical terms, this includes:

- Control over data and data flows

- Governance of digital infrastructure (cloud, telecom, compute)

- Rule-setting power over platforms and emerging technologies

- Reduced systemic dependence on non-European technology providers

The ambition is not dominance, but resilience: the ability to act when geopolitical, economic, or technological conditions shift.

Why the Challenge Has Become Structural

As the global economy moves toward a more fragmented, post-globalized digital order, digital sovereignty has shifted from a privacy debate to a hard security and competitiveness issue.

1. Structural dependence on foreign providers

Large parts of Europe’s cloud, AI, platform, and semiconductor ecosystems depend on non-European actors. This creates exposure, not only to pricing and tarifs power but also to extraterritorial legislation and political leverage.

2. Missing European scale players

Europe produces strong research and startups, but too few global digital champions. Critical players in segments such as cloud business, advanced AI infrastructure, leading-edge chips, mobiles, hardware of all sorts, etc. remain structurally underrepresented.

3. Policy fragmentation inside the EU

Diverging national strategies weaken collective bargaining power and slow down coordinated infrastructure and market development.

4. Technology as a geopolitical instrument

Digital infrastructure provided by hyperscalers such as Microsoft, AWS and Google has become a vector of influence. Extraterritorial access rights, supply chain chokepoints, and standards-setting are now tools to influence and at times bully other geopolitical players. Or at worst sabotaging the work of respectable institutions and individuals such as seen in luckily still singular instances.

5. Supply-chain security

In the complex digital world there are many components and layer working together. This requires additional insight and visibility across hardware, firmware, and software layers. Unknown components are ungovernable risks.

6. Resilience against hybrid threats

The risk also comes from increasing dependency on control over algorithms, identity systems, and critical digital services for example in election contexts. From Social media platforms for sharing fake news to gaining access through backdoors – at times intended with a nations law all constantly challenge nations, companies and individuals alike.

The EU Policy Architecture

Europe has not been passive. A dense regulatory and strategic framework limiting global players of all sorts is emerging. It’s countering risks and threats within the Union and at times beyond.

Established instruments

- GDPR – Global benchmark for data protection and extraterritorial accountability

- Digital Markets Act (DMA) – Competition rules for gatekeeper platforms

- Digital Services Act (DSA) – Transparency and accountability for digital platforms

- NIS2 Directive – Cybersecurity obligations for critical services

- Data Governance Act (DGA) – Trusted data sharing across sectors

- European Chips Act – Rebuilding semiconductor capacity

- AI Act – Risk-based governance of artificial intelligence

- European Health Data Space – Cross-border health data access

- GAIA-X – Federated cloud governance aligned with European values

- EU Cybersecurity Strategy – Deeper operational coordination and joint defense

Regulation alone, however, does not create sovereignty. Capabilities do.

The Dimensions of Digital Sovereignty

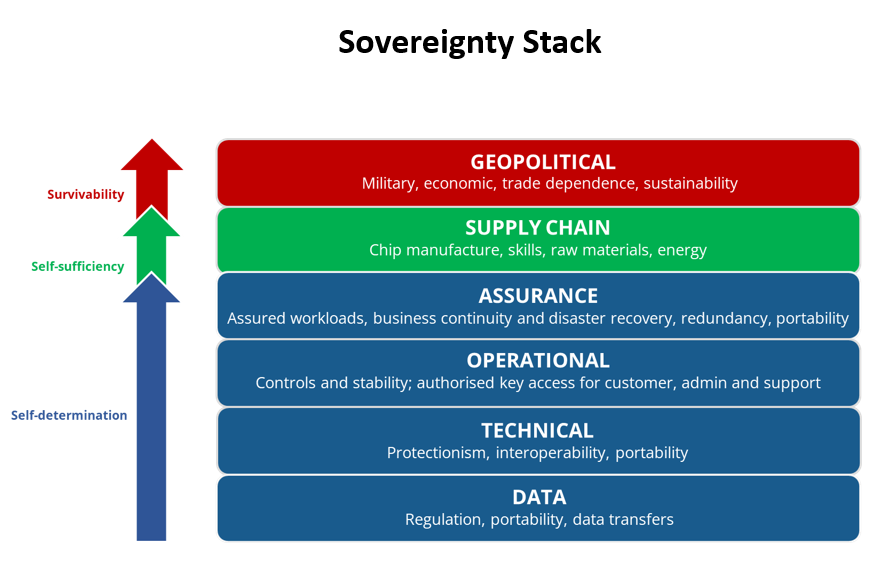

A widely cited framework by IDC describes digital sovereignty as a multi-layered stack:

The Evolution of Digital Sovereignty: Moving Beyond Data and Cloud” (Rahiel Nasir, IDC, January 13, 2023)

- Data sovereignty

Control over how data is collected, processed, stored, and used including AI training data and model governance. - Technical sovereignty

The ability to run services, applications and workloads independently of a provider’s infrastructure or software, protected from extraterritorial interference. - Operational sovereignty

Visibility and control over provisioning, performance, and physical and digital access to infrastructure. - Assurance sovereignty

Independent verification of system integrity, security, and resilience, especially for critical services. - Supply-chain and skills sovereignty

Resilient digital supply chains, local innovation capacity, and knowledge transfer that enables long-term competitiveness. - Geopolitical sovereignty

Recognition that digital systems are now part of a nation’s critical infrastructure and strategic posture.

This evolution reflects a simple truth: data alone is no longer the battlefield, the entire stack is.

Sovereignty Is the Ability to Decide

Digital sovereignty is often framed as a defensive concept, however:

- It does not promise technological supremacy.

- It does not eliminate global interdependence.

- And it does not protect against bad decisions.

What it does provide is something more fundamental: the ability to decide, to choose, to set rules, to manage risk, and to act in line with democratic values even when dependencies are tested.

In the digital age, sovereignty is no longer anchored in territory or resources in the ground.

It is anchored in control over data and systems, mastery of complexity, and the freedom to choose cooperation without coercion when it comes to digital infrastructure and services.